How excessive percentage-based fees can warp risk and return

Investing is all about risk and return: get the balance right and be handsomely rewarded. The structure of percentage-based fees often tips those scales in favour of investment platforms and fund managers. Once their asset base grows large enough to cover operating costs, natural market growth and guaranteed inflows create enormous profits, no matter what the outcome for investors.

Think about it this way: at least one-third of returns goes to platforms and managers.

Take a platform, wrap or master trust that has grown to $60 billion in funds under management while charging an average 1 per cent fee. This equates to an enormous $600 million in revenue a year, in exchange for collating various investment options and providing performance and tax reporting for investors.

The costs of running the service (IT, security, web design, staff, rent, compliance and so on) remain largely flat. Meanwhile, fees naturally rise with the value of the underlying investments, which have (in aggregate) grown over time as the Australian economy has expanded.

If we use a conservative 5.7 per cent average annual return (based on a balanced fund’s return over the 10 years ended December 31, 2015), our hypothetical platform would receive an extra $34.2 million in annual fees – for delivering no extra value to investors.

The majority of fund managers derive great benefit from percentage-based fees, even when they don’t deliver strong performance to investors. The near 40 per cent rise in the S&P/ASX 200 over the five years ended January 3, 2017, has delivered millions of dollars in extra fees to Australian equity managers who have failed to hit their performance targets or masqueraded as active managers while hugging the index.

Investors lost. The industry won. The former bore the bulk of the risk, the latter took the bulk of returns.

A slow change underway

For better or worse, this situation is slowly changing.

Investment returns are unpredictable but investment fees are constant. Small variances can add up to enormous differences as returns compound over time. This is why investors need to carefully assess the level of fees, their structure, and who bears the bulk of risk and return under different market conditions.

Fund managers can justify a percentage-based fee structure if they deliver what’s on the label and their prices remain competitive. A well-respected, professional fund manager is absolutely appropriate for those investors who require their expertise and have done some homework.

On the other hand, newer structures, such as exchange-traded funds, deliver market beta for just a few basis points. They have set a new baseline: active fund managers need to deliver a net return (after fees and taxes) consistently above this for investors just to break even with them.

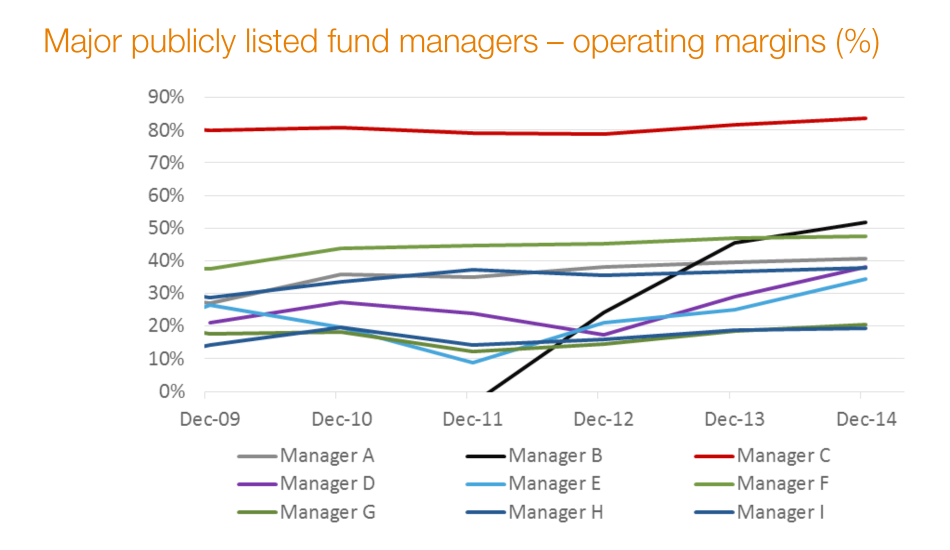

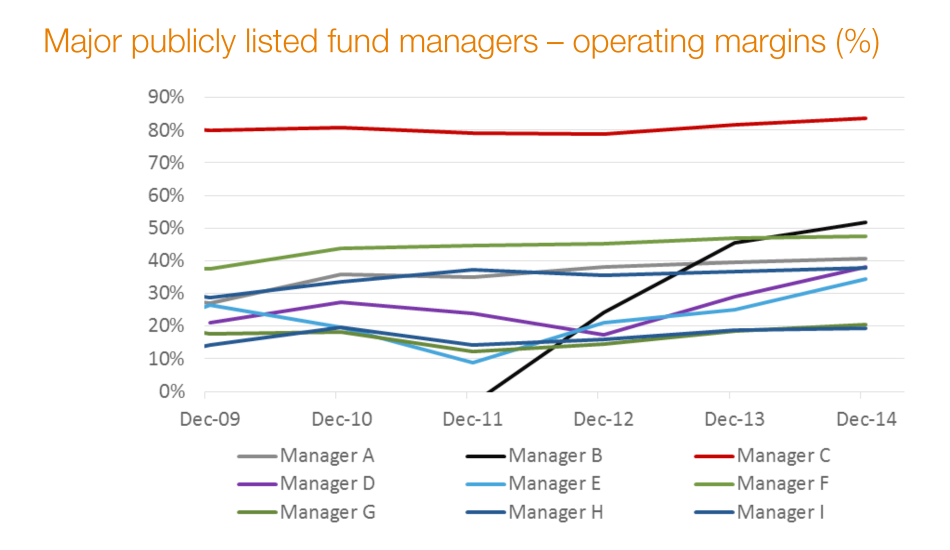

The industry’s healthy operating margins suggest competition will eventually lead to restructured or lower fees – something that is already occurring in the institutional sector, where large super funds have greater bargaining power.

There is, however, nothing to defend the hefty percentage-based fees charged by the $700 billion investment platform, wrap and master trust industry.

Platforms bring together a range of underlying fund manager products and offer the benefit of bulk administrative services to the people responsible for selling the products. They exist to make it easy for financial advisers to sell products with as few clicks as possible. They do not care about the investor. Imagine if doctors told patients they could perform surgeries only with whatever medical tools the clinic’s head office had ordered.

Leaving aside common conflicts of interest (many of these underlying managed funds are owned by the platform’s parent company), this is no longer an innovative service that can justify high percentage-based fees.

Popular investment platforms still typically scrape between 0.5 per cent and 2 per cent from investors’ portfolios every year. That’s the equivalent of $3.5 billion to $14.2 billion across more than $700 billion in assets.

These platform fees are often higher than the cost of underlying funds management. That would be like Apple iTunes charging an ongoing fee greater than the cost of the music and movies people buy. So the service aimed at making performance tracking and administration easier is often destroying that same performance with excessive fees.

Alternatives emerge

Just as low-cost exchange-traded funds have posed clear questions about the value of high-cost active fund managers, a new wave of low-cost fintech innovators is now attacking the value proposition of high-cost platforms.

These new providers don’t need to protect high operating margins; technology is allowing them to offer similar or superior service to other platforms at a lower price. At the same time, the public is demanding greater access to and control over their own data (whether held by government or a financial institution such as a bank) and the ability to shift providers easily.

Many of these new administrative and performance-tracking services can be accessed with low, flat fees. The value of flat fees is more transparent than high percentage-based fees and the economies of scale delivered by a growing asset base aren’t entirely pocketed by the service provider.

These new services are finally putting power back into the hands of investors and re-balancing the scales of risk and return. That’s a win for investors. But it’s also a win for those in the industry who deliver on their promises.